REEF is giving me much to contemplate. The exhibition raises fascinating questions about the Earth itself as an art space, and more troubling ones about the human impact on the sea. There’s also the opportunity to explore the show’s connection to the Brighton Photo Biennial which, with its theme of Community, Collectives and Collaborations, is fuelling my interest in dissolving boundaries between art and politics. But I’ve had a request for more about Neptune, and reflections on my guiding star seem a good place to start my journey. So as not to immediately frighten anyone off, I’ll begin with the astronomical facts. They are poetic enough in themselves, but be warned: this post ends with a flash of my astrological license!

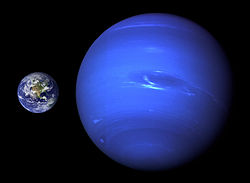

To begin, though, with sober statistics: over fifty seven times the volume of Earth, but only seventeen times greater mass, Neptune is classed as both a gas and ice giant. For all its great size, it rotates quickly; while it takes 164 Earth years to orbit the sun, its ‘day’ is just 18 hours. Largely atmosphere, the planet is composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, traces of methane absorbing red light and lending the planet its luminous blue colour – though it is speculated that an unknown chromophore is responsible for the tint of the clouds. Invisible to the naked eye, this lustrous behemoth was discovered by mathematical prediction: the erratic orbit of Uranus suggested the gravitational pull of an outer planet, and thanks to the calculations of French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier, Johann Galle located the culprit on Sept 23 1846, from his observatory in Berlin. In fact, Galileo had first observed Neptune in 1612, calling it ‘the blue star’, but as he didn’t twig it was a planet, is not credited with discovering it. (Here I simply must insert a little joke I heard at a talk last week by Israeli peace activist Ruth Edmonds – when asked how she refers to Israel-Palestine, she said ‘Pluto’, after the small planet of highly disputed status . . . ) Sorry about that – astro-politico geek moment over, we can return to Le Verrier, who initially suggested naming his new planet for the Roman god of the sea. Successfully locating a gas giant must have gone to the astronomer’s ego though, for he was soon campaigning to instead christen the planet after who-else-but-himself. In the end, the Parisian had to settle for the slightly less immortal recognition of a medal from the Royal Society: Neptune, and its various global translations, was adopted by consensus – though be careful how you go in Greece, where the ‘Sea King Planet’ is defiantly known as Poseidon.

Governed by extremes, Neptune is a planet of exorbitant beauty and power. Its fiercely cold surface is whipped by the fastest winds in the solar system: if there isn’t a Mod badge for Neptune, there ought to be – one of its prominent cloud formations is known as ‘the Scooter’ for its speedy circumnavigation of the planet. Elsewhere, goths and Oya worshippers will be pleased to note, rage storms large enough to engulf the Earth. Beneath this turbulent veneer, Neptune’s foggy atmosphere is thought to eventually merge with an icy mantle, though the technical term is misleading – the planet’s middle layer is in fact a hot dense fluid composed of ionised water and ammonia. Smelly and scalding it may be, but Marilyn Monroe and Eartha Kitt would have loved it: close to the planet’s 5000 °C heart it is conjectured that diamond crystals rain like hailstones into a slushy diamond sea, sailed by massive diamond-bergs. At the centre of this dazzling ocean is the planet’s rocky core, a jagged furnace of iron, nickel and silicates, thought to be slightly larger than Earth. As for rings, Neptune has six thin ones, plus a slender necklace of moons. For over a century the planet was thought to have just one satellite – Triton, the coldest known world in the solar system – but as of 2013 thirteen more, much smaller moons have been counted, the last still unnamed, the rest suitably honouring Greek and Roman water deities.

Life as we know it cannot exist on Neptune, but the planet has long animated the human imagination, not least that of astrologers. At the time of its discovery – and now again since the controversial demotion of Pluto to ‘dwarf planet’ status – the blue giant was the last planet of the solar system (and in any case, Pluto’s eccentric orbit means that sometimes Neptune outlies it). This fringe existence caused infamous occultist Aleister Crowley to call Neptune ‘a lonely sentinel patrolling the confines of our camp’. Crowley associated Neptune’s solitude with psychic abilities and perverse undoings, but I will reflect on his characteristically astringent theories in a future post. For now, having staked my astrological flag on thoroughly dubious soil, I will leave you safely in the marvellous gravitational field of Derek Jarman.

For naturally, upon encountering the magnificent word ‘chromophore’ – suggesting a kind of cosmonautical sign language of hue – I reached for Jarman’s lyrical autobiography, Chroma: A Book of Colour – June ’93 and, like Triton by the giant, was immediately captured by the iconic British artist’s meditations on blue:

In the pandemonium of image

I present you with the universal Blue

Blue an open door to soul

An infinite possibility

Becoming tangible.

Absent by name in the chapter, Neptune is wholly present, to me, not just in such lucid invocations of its spiritual associations, but a moment of uncanny prophecy – losing his sight and his life to AIDS-related illness, Jarman, ever the visionary campaigner, asks:

What do I see

Past the gates of conscience

Activists invading Sunday Mass

In the cathedral

An epic Czar Ivan denouncing the

Patriarch of Moscow

Perhaps Pussy Riot read Chroma – why not, Jarman loved punk – but the weird personal resonance with my residency event, Sea Changers, bringing three artist-activists to the vestry of St Paul’s Brighton, is currently giving me the scootery shivers. I need to immediately seek out Jarman’s classic films Blue and The Tempest and watch them wrapped in a duvet of warm clouds – more from Crowley and other blue angels next time.